All in on event sourcing

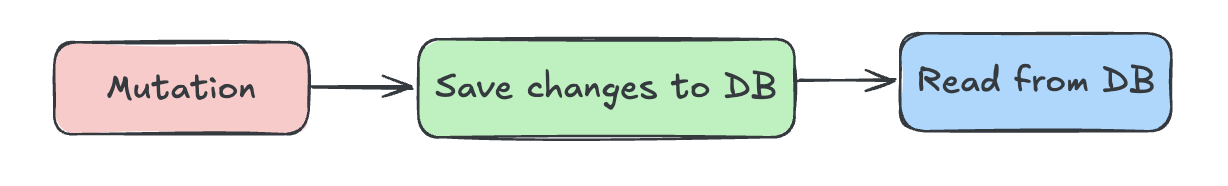

The idea of event sourcing is completely different from what we usually build. In a simple CRUD application, the flow looks like this:

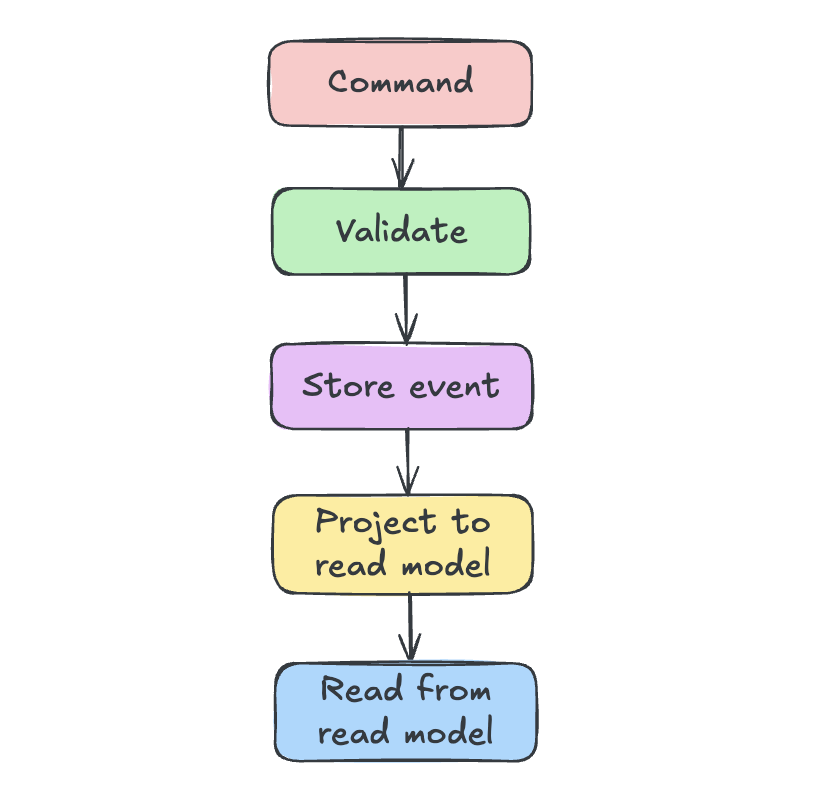

You can see how the entire world revolves around the current state in your database - the end result of countless actions, with no history of how it got there. Let’s see the difference event sourcing makes:

You can see how the entire world revolves around the current state in your database - the end result of countless actions, with no history of how it got there. Let’s see the difference event sourcing makes:

Instead of storing “Participant has balance of 300 chips” you store what actually happened:

-

ParticipantJoined(+1000 chips) -

BetPlaced(-200 chips) -

HandWon(+400 chips)

Here you focus on the sequence of events that led to the current state, rather than the state itself. For example, if you want to know the current balance of a participant, you don’t look it up in a database like that:

SELECT balance FROM participants WHERE id = 'participant-123';Instead, you replay the events related to that participant:

-

Start with a balance of 1000 chips (from

%ParticipantJoined{amount: 1000}) -

Subtract 200 chips (from

%BetPlaced{amount: 200}) -

Add 400 chips (from

%HandWon{amount: 400})

Resulting in a current balance of (1000 - 200 + 400) = 1200 chips.

That’s the core idea of event sourcing. Instead of storing the current state, you store what happened, and you get the current state by replaying those events. Your history is your data, and as long as you have it, you can always reconstruct where you are and how you got there.

Today I’ll show you the fundamentals of an event-sourced system using a poker platform as an example, but first, why would you choose this over plain CRUD?

Is it worth the trouble?

From the diagram above, event sourcing may look more complex than CRUD, and it is. While it offers significant advantages, it comes with tradeoffs. It adds complexity, requires more infrastructure, and your team needs to learn a new paradigm. Before committing, ask yourself:

- Does your platform have complex business rules that need to be explicit and traceable? (e.g., poker rules, betting logic, player actions)

- Does your platform need an audit trail for compliance or debugging? (e.g., tracking every action taken by players to ensure fair play)

- Do your functional requirements include reconstructing past states or replaying events? (e.g., reviewing a player’s actions during a tournament)

If you answered “yes” to any of these questions, event sourcing might be a good fit for your platform or to certain parts of it.

In terms of poker platform, event sourcing is definetely helpful. Poker has complex rules, requires audit trails for fairness, and often needs to reconstruct game states for reviews by moderators. Event sourcing provides a natural way to cover these requirements.

Defining the domain boundaries

If you see the value in event sourcing for your platform, the next step is to define your domain boundaries. It’s important to do this before writing code because changing boundaries later in an event-sourced system can be painful. If you want a deep dive on boundary design, I highly recommend this video.

Now, let’s look at a real example where I’ve split my poker platform into several boundaries, each with its own responsibilities. You’ll see that not all of them need event sourcing and it depends on the domain. And don’t worry if you’re not familiar with poker, the focus is on structure, not the game itself:

-

Table Management (ES) - creating, configuring and managing poker tables. This is where poker logic lives.

-

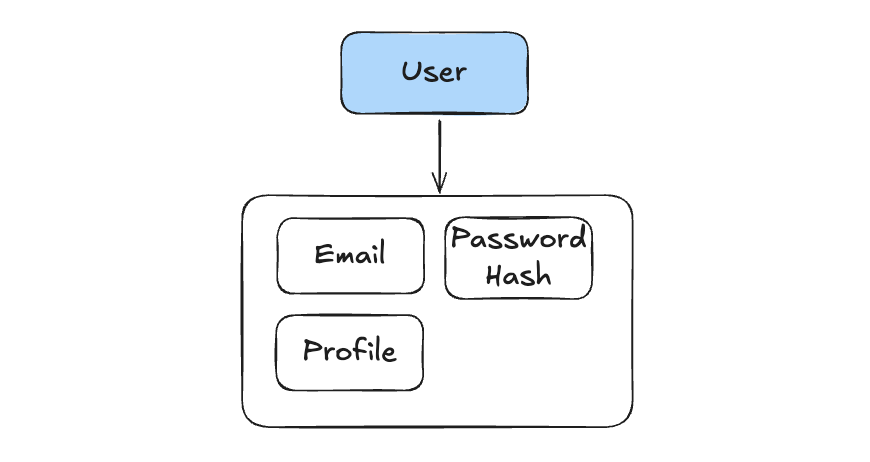

User Management (CRUD) - handling user accounts and profiles. This is where user logic lives, and usally it doesn’t need event sourcing because user

data is relatively simple and doesn’t require complex audit trails.

-

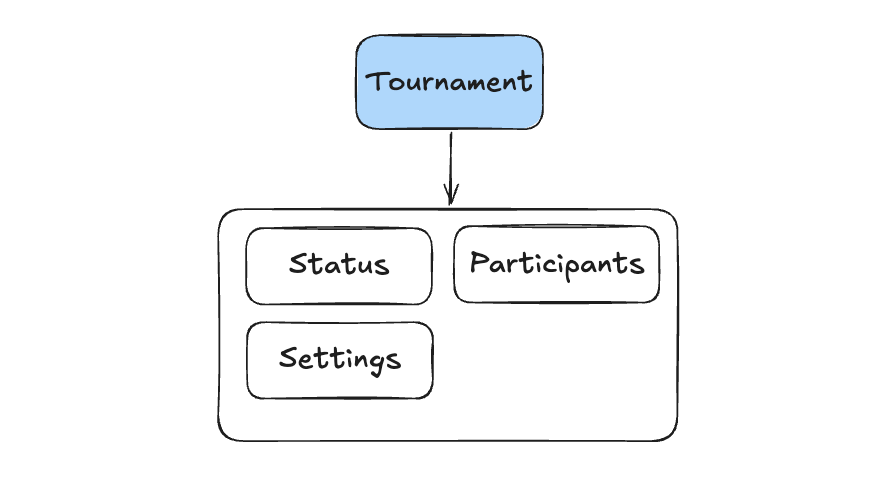

Tournament Management (ES) - organizing and running poker tournaments. This is where tournament logic lives.

Here we have two event sourced boundaries (Table Management and Tournament Management) and one CRUD boundary (User Management). This hybrid approach allows us to apply event sourcing where it adds the most value while keeping other parts simple.

The building blocks

Now it’s time to define the building blocks of each event-sourced system. For this example, I will use Commanded - an Elixir library for building event-sourced applications. It gives you the infrastructure and you write the business logic.

Event store

The core of an event-sourced application is the event store. It’s just a log of events, stored in order. Unlike CRUD, where data lives in tables representing current state, here you only have events. From them, you can rebuild state, create read models, debug problems, or analyze historical behavior.

Aggregate

The business logic boundary like Table or Tournament. It’s a cluster of related objects treated as a single unit that protects your business rules. Think of a poker table with id “123”: participants, hands, pots, community cards. When a request comes in to a specific aggregate, the state is rebuilt from events and loaded into memory. From there, it validates requests directly, no database queries needed:

defmodule Poker.Tables.Aggregates.Table do

defstruct [

:id,

:creator_id,

:status,

:settings,

:participants,

:community_cards,

:pots,

:deck,

# ... rest of the state

]

endCommand

Request to change aggregate’s state like JoinParticipant. It represents intent, something that should happen. A command contains all the data it needs and targets a specific aggregate by its unique identifier:

defmodule Poker.Tables.Commands.JoinParticipant do

use Poker, :schema

embedded_schema do

field :user_id, :binary_id

field :table_id, :binary_id # <-- the aggregate root id

field :participant_id, :binary_id

field :starting_stack, :integer

end

def changeset(attrs) do

%__MODULE__{}

|> Ecto.Changeset.cast(attrs, [:participant_id, :user_id, :table_id, :starting_stack])

|> Ecto.Changeset.validate_required([:participant_id, :user_id, :table_id])

end

endEvent

An immutable fact about something that did happen in past tense: ParticipantJoined. Once events appear, they’re appended to a log, never modified, never deleted:

defmodule Poker.Tables.Events.ParticipantJoined do

@derive {Jason.Encoder,

only: [

:id,

:player_id,

:table_id,

:chips,

:initial_chips,

:seat_number,

:is_sitting_out,

:status

]}

defstruct [

:id,

:player_id,

:table_id,

:chips,

:initial_chips,

:seat_number,

:is_sitting_out,

:status

]

endCommand Handler

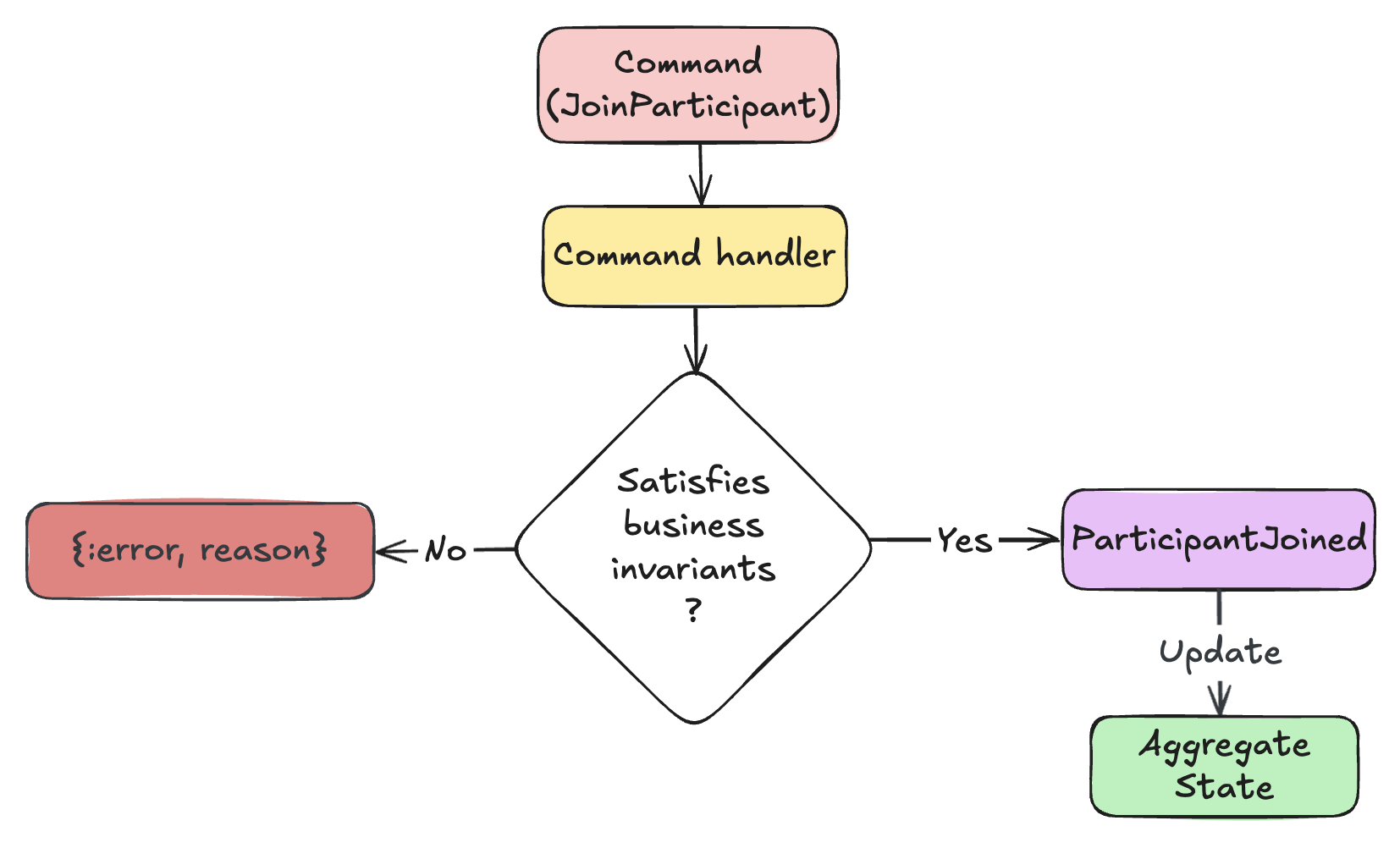

Function that takes a command, validates it against the current aggregate state, and either rejects it or produces an event:

def execute(%Table{status: :live}, %JoinParticipant{}) do

{:error, :table_already_started}

end

def execute(

%Table{participants: participants, settings: settings},

%JoinParticipant{} = command

) do

if length(participants) < settings.max_players do

%ParticipantJoined{

id: commmand.participant_id,

player_id: commmand.player_id,

table_id: commmand.table_id,

chips: command.starting_stack,

seat_number: length(participants) + 1,

status: :active

}

else

{:error, :table_full}

end

end

See how it works? We validate the command without touching the database, the aggregate state is in memory only. No queries, no joins, just pure business logic. If the command is valid, we return a ParticipantJoined event. If not, we return an error tuple.

Aggregate State

As you now understand, an aggregate is a process that holds the current state of a specific entity. This state is rebuilt by replaying its events, and updates whenever a new event is produced:

def apply(%Table{participants: participants} = table, %ParticipantJoined{} = event) do

new_participant = %{

id: event.id,

player_id: event.player_id,

chips: event.chips,

seat_number: event.seat_number,

status: event.status

}

%Table{table | participants: participants ++ [new_participant]}

endEvent handler

Often your application needs to react to events, such as sending an email or notifying a separate service. Event sourcing naturally supports this by allowing you to handle events asynchronously through subscriptions to the event store, naturally separating your side effects:

defmodule Poker.Notifications.EventHandler do

use Commanded.Event.Handler,

application: Poker.App,

name: __MODULE__

def handle(%GameEnded{winner_id: winner_id, prize: prize}, _metadata) do

winner = Accounts.get_user!(winner_id)

Poker.Email.send_game_won(winner.email, prize)

:ok

end

endProjection

The read model built from events. You can think of it as a materialized views of your event log. This is your read side, and unlike aggregates, it’s all about making queries fast. Projections listen for events and update a queryable store, like a Postgres table or a NoSQL collection:

defmodule Poker.Tables.Projectors.Participant do

use Commanded.Projections.Ecto, name: __MODULE__

project(%ParticipantJoined{} = joined, fn multi ->

Ecto.Multi.insert(multi, :participant, %Participant{

id: joined.id,

player_id: joined.player_id,

table_id: joined.table_id,

chips: joined.chips,

seat_number: joined.seat_number,

status: joined.status

})

end)

end

Here, the Participant projection listens for ParticipantJoined events and writes to a regular Postgres table. Now your client can query participants with plain SQL:

SELECT * FROM participants WHERE table_id = 'table-123';

# Result:

| id | player_id | table_id | chips | seat_number | status |

|--------------|--------------|--------------|-------|-------------|---------|

| participant-1| player-456 | table-123 | 1000 | 1 | active |

| participant-2| player-789 | table-123 | 1500 | 2 | active |If you need to have different read models (e.g., for reporting, analytics, or different views), you can create multiple projections from the same event stream, like for analytics:

defmodule Poker.Tables.Projectors.Analytics do

use Commanded.Projections.Ecto, name: __MODULE__

project(%ParticipantJoined{} = joined, fn multi ->

Ecto.Multi.update_all(

multi,

:participant_count,

from(p in ParticipantCount, where: p.table_id == ^joined.table_id),

inc: [count: 1]

)

end)

project(%HandStarted{} = finished, fn multi ->

Ecto.Multi.update_all(

multi,

:hand_count,

from(p in ParticipantCount, where: p.table_id == ^finished.table_id),

inc: [count: 1]

)

end)

endIt will allow you to quickly query the analytics for each table:

SELECT participant_count, hand_count FROM participant_counts WHERE table_id = 'table-123';

# Result:

| table_id | participant_count | hand_count |

|--------------|-------------------|------------|

| table-123 | 2 | 48 |Notice how each projection is built for its specific use case. You can even use different storage for different projections: Postgres for structured data, Redis for hot data like leaderboards, Elasticsearch for full-text search. Your write side stays the same (storing the list of events), while your read side gets exactly what it needs by subscribing to them.

Putting building blocks together

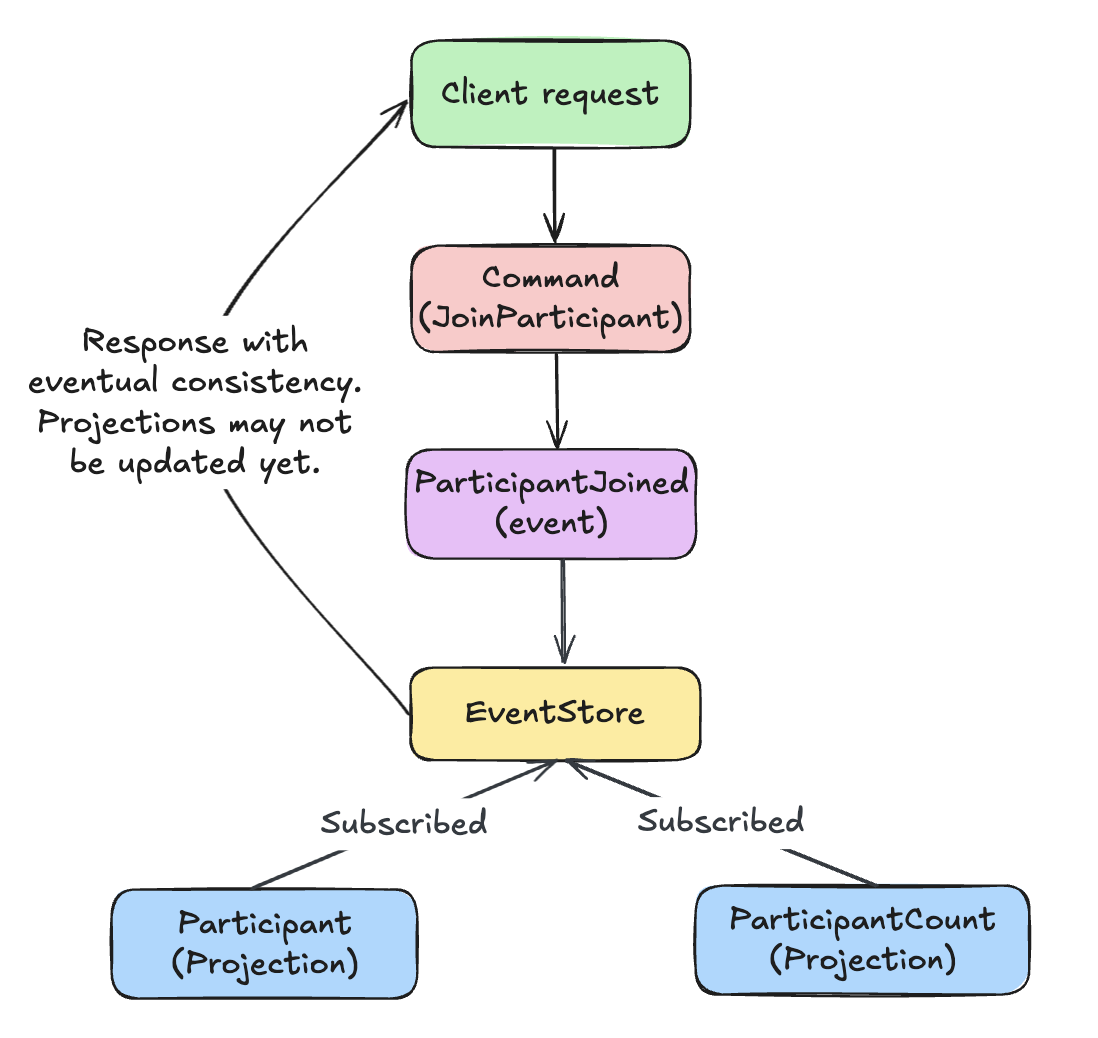

Now that we have all the building blocks defined, let’s see how they interact in a complete flow when a participant joins a poker table:

-

A client sends a

JoinParticipantcommand to the Command Handler. -

The Command Handler loads the current state of the

Tableaggregate by replaying its events. - The Command Handler validates the command against the aggregate state.

-

If valid, it produces a

ParticipantJoinedevent. - The event is appended to the event store.

- The aggregate state is updated by applying the new event.

Then, projections listen for the ParticipantJoined event and update their respective read models. But here’s the catch - by default, this happens asynchronously or eventually consisent:

The response returns as soon as the event is stored, while projections update in the background. If the client queries immediately, the participants data might not be there yet.

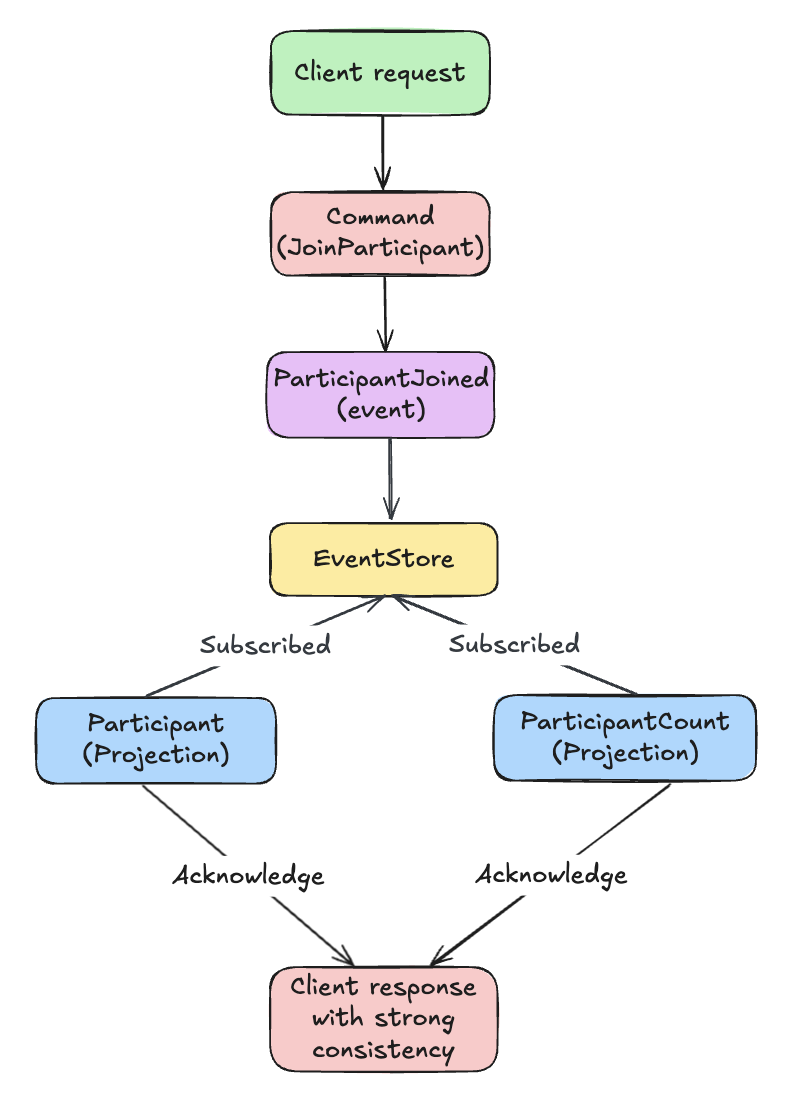

If you need the client to see updated data immediately (strong consistency), there’s a mechanism for that. Projections send an acknowledgment back to the command, and the response waits until all acknowledgments arrive:

Waiting for projections to update adds latency. Whether you need strong consistency or can live with eventual consistency depends on your use case.

Multi-aggregate coordination

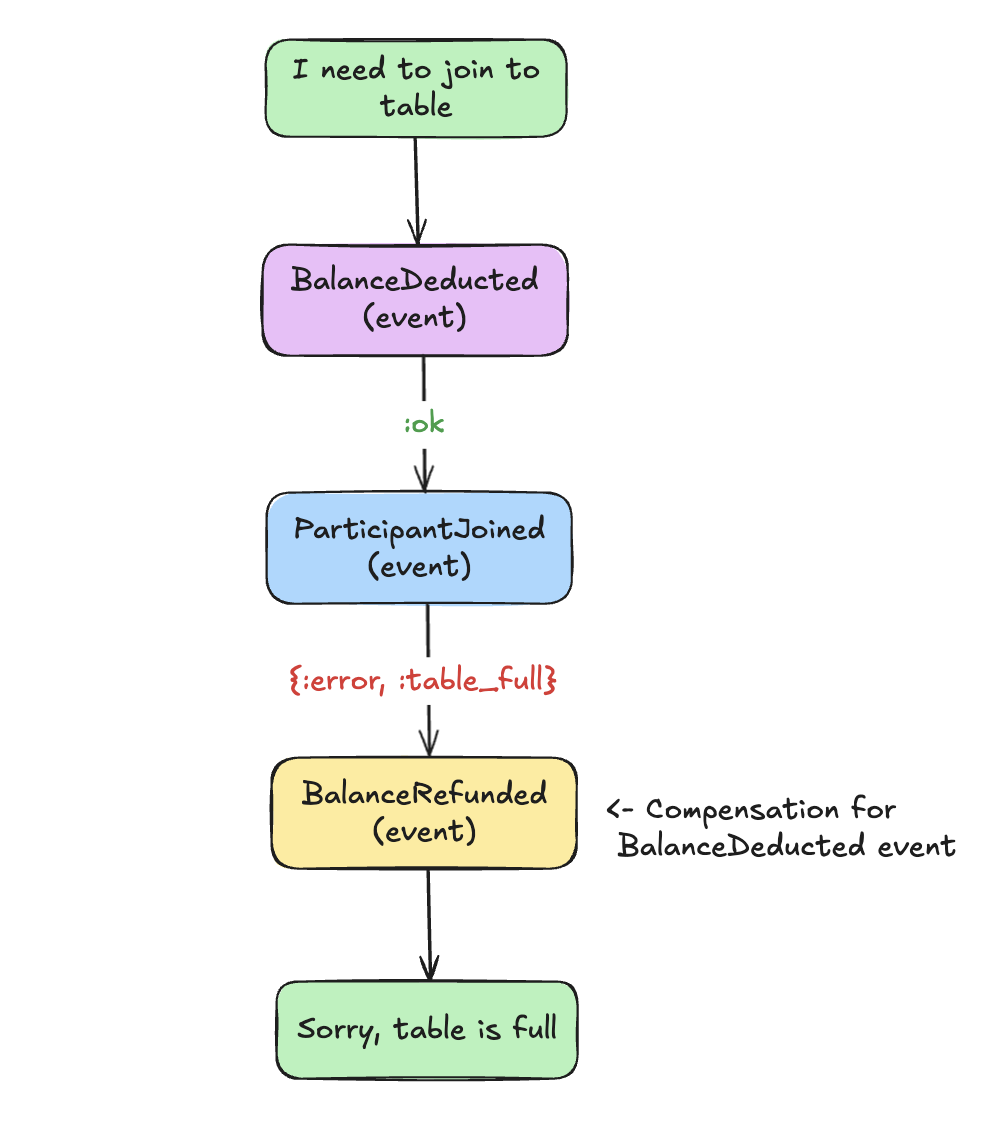

At this point, you know how to define aggregates, build logic inside them, and understand how projections work. But sometimes a single user action touches multiple aggregates:

- Deduct buy-in from user balance (Wallet aggregate)

- Register participant (Tournament aggregate)

What if step 1 succeeds but step 2 fails because the table is full? You can’t delete events, they’re immutable. Instead, you dispatch compensation events that reverse the effect of previous ones. Think of it like a corrector pen on paper: the original mark stays, but you write over it:

This works for most cases, and you probably won’t need more. But some processes outlive a single request, like tournaments that run for hours. For these, there’s a mechanism called “Process manager”. It’s a long-lived process that listens to events, dispatches commands, and handles failures along the way.

For example, a tournament process manager listens for TournamentStarted event, creates tables, rebalances tables when players get eliminated, and distributes prizes at the end. The mechanics are the same as I showed above, but process managers also come with built-in logic for handling retries and managing compensation events when something fails.

Challenges

I’ve mentioned some challenges throughout the article, but let’s summarize them:

- Increased complexity - event stores, aggregates, and projections are what make event sourcing possible. These abstractions can make debugging and fixing issues much more complicated compared to CRUD.

- Event versioning - as your domain evolves, event structures will definitely change. Upcasting old events to new formats adds complexity, and you need to handle it carefully.

- Storage growth - the event log grows quickly if you have complex system and lots of users.

- Snapshotting - to avoid replaying thousands of events, you snapshot aggregate state periodically. It’s another abstraction you need to manage to avoid situations where your server takes forever to start.

- Eventual consistency - writes and reads are separated, so data might not be there yet when you query it.

- Querying - no ad-hoc SQL against current state. You need a projection for each query use case.

The good news: established libraries like Commanded handle most of this for you. Don’t let these challenges scare you off.

Conclusion

This pattern changes how you think about systems and their boundaries. You may find that some parts of your system already need it, and that’s will be a sign that you should try it. Before writing your own implementation, use existing solutions like Commanded. The abstractions and conventions will help you understand the architecture faster.

Good luck, and go all in!